STORY OF THE MONTH

CAN YOU SP0T THE MISTAKE?

Jan 2026

Jan 2026  Javier Rey Domínguez

Javier Rey Domínguez

Last year, we went over the different strategies to distribute entanglement using quantum repeaters. There, we talked about a key technique at the core of second-generation and third-generation repeaters: quantum error correction (QEC). This month, we are going to take a closer look at how error correction works, how is it different for quantum information, and what are the particularities of applying QEC to quantum repeater schemes, specifically those of second generation.

Classical error correction

Picture this. You walk your little brother to school, and right as he is about to go in, you remember something. But he is now across the street, busy with noisy cars and chatty students. You shout at the top of your lungs:

“BY THE WAY! I HAVE SOME THINGS TO DO, SO I’LL PICK YOU UP 15 MINUTES LATER THAN USUAL! WAIT FOR ME AT THE BUS STOP!”

He looks back at you. He’s heard you shouting at him, but his face tells you he hasn’t understood what you said. So, you go again:

“I WILL PICK YOU UP 15 MINUTES LATER THAN USUAL! WAIT AT THE BUS STOP!

After a couple of seconds, you see him nod. He understood.

What you have done there is at the core of error correction. You have made your message clearer by adding redundancy.

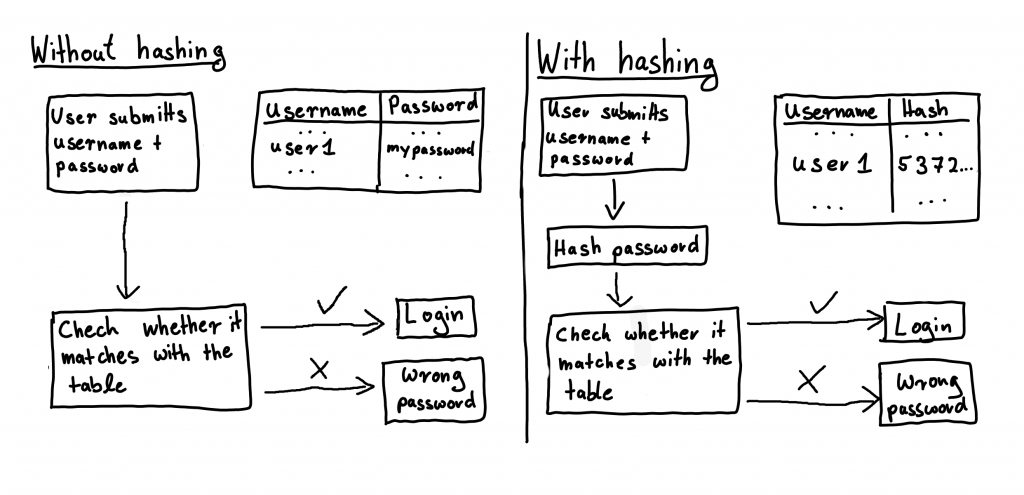

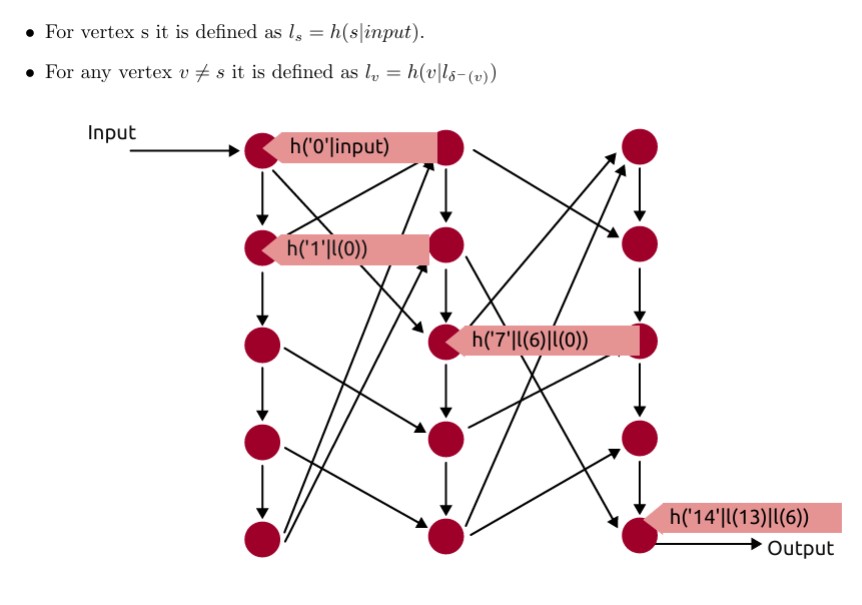

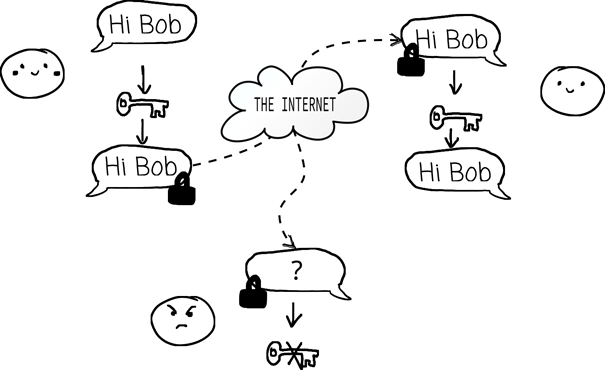

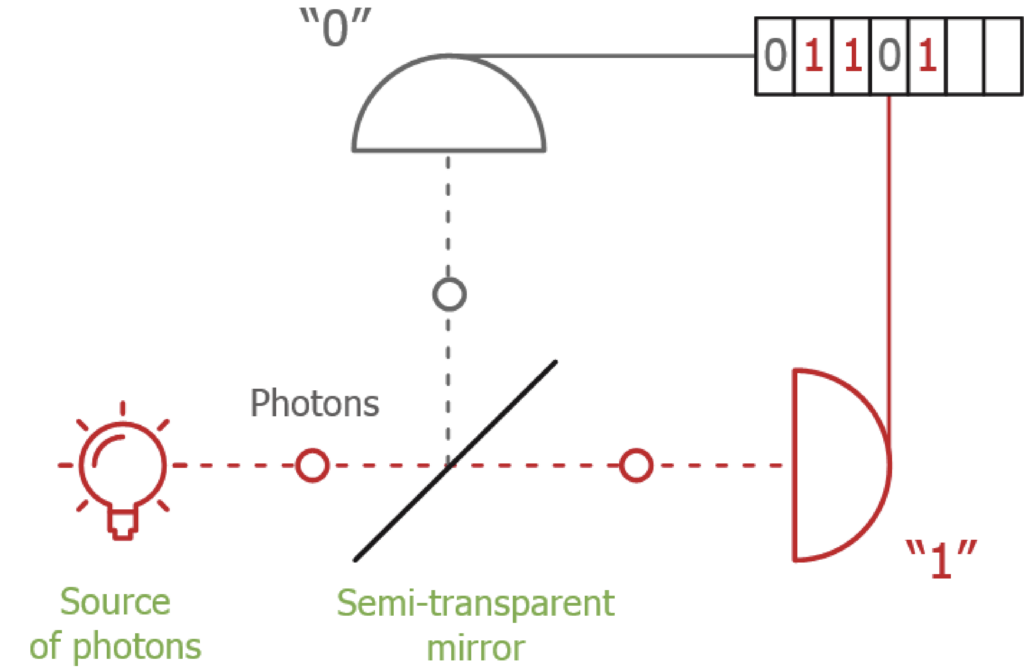

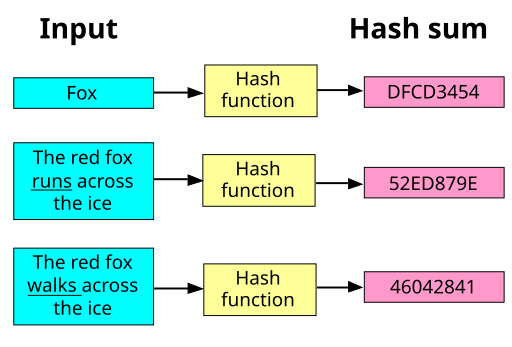

This is exactly what computers and communications devices use. For instance, say they need to transmit a bit value, i.e. a 0 or a 1. But the channel they are using flips the bits on occasion. That is, with some probability, zeroes turn to ones and ones, to zeroes. A simple way to make sure the receiver gets your bit to, simply, send it several times. Instead of sending “0”, you send “000”, and instead of sending “1”, you send “111”. Then, even if one bit flipped, the receiver can see “010” and guess that you sent “000”, that is, “0”. This is called a repetition code. Of course, the three-bit version cannot help if more than one bit flip happens, but if the probability of this is low enough, it is a practical solution.

Naturally, the error correction codes that are used in practice are often more complex than this. For instance, you might want to rearrange the bits so that, if bursty errors affecting consecutive bits are common, they don’t erase the information of entire blocks of data. This is called scrambling. Nevertheless, the core idea remains the same: you add redundancy in some structured way, and then use that redundancy to recover your original data.

Quantum error correction

Moving on to quantum error correction, things get more complicated. First, we must deal with the no-cloning quantum theorem, which means we cannot simply copy the information several times (you can read more about this in other stories, like Shashank’s “Weaving the Quantum Web: Bob’s Vision for a Connected Future”). What is more, we can’t perform arbitrary measurements when we want to check for errors, as that could collapse the state. Finally, the types of errors in quantum information are more varied, and we need to take them all into account.

Fortunately, all these problems have solutions. In fact, the field of quantum error correction theory is constantly advancing and innovating, so we can be sure that the quantum computers of the future will rely on great QEC strategies.

Quantum repeaters with QEC

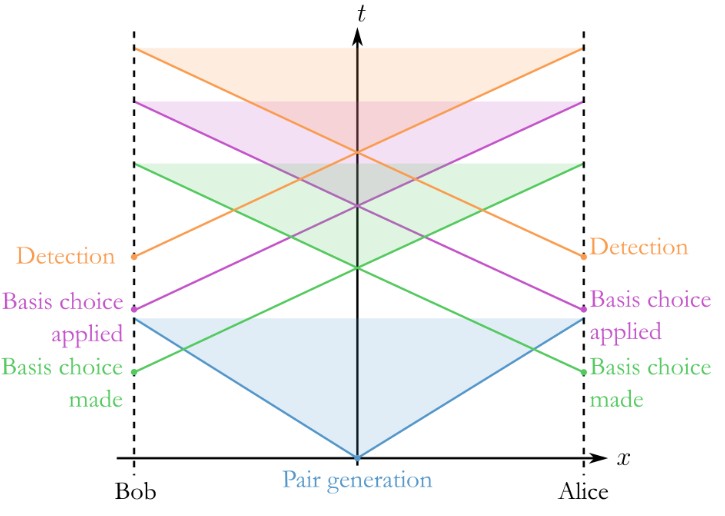

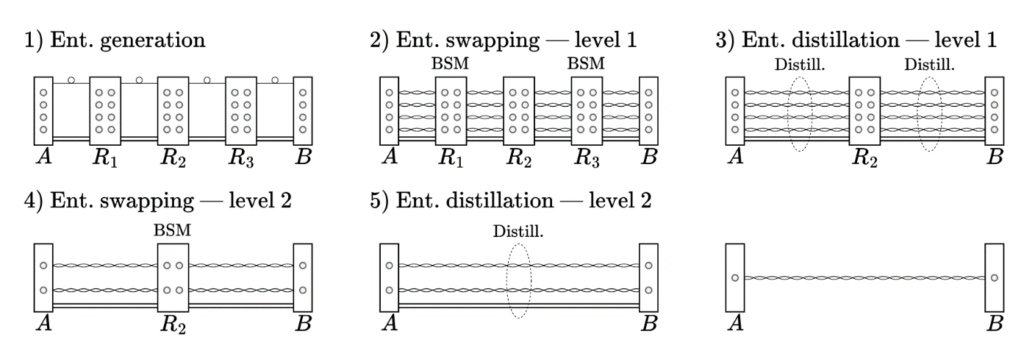

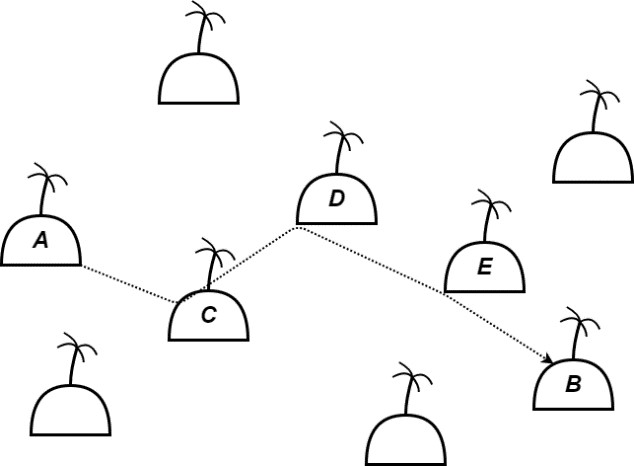

If you need to refresh your memory about how quantum repeaters work, you may read my story from 2025, “About scalable entanglement distribution and ropes”.

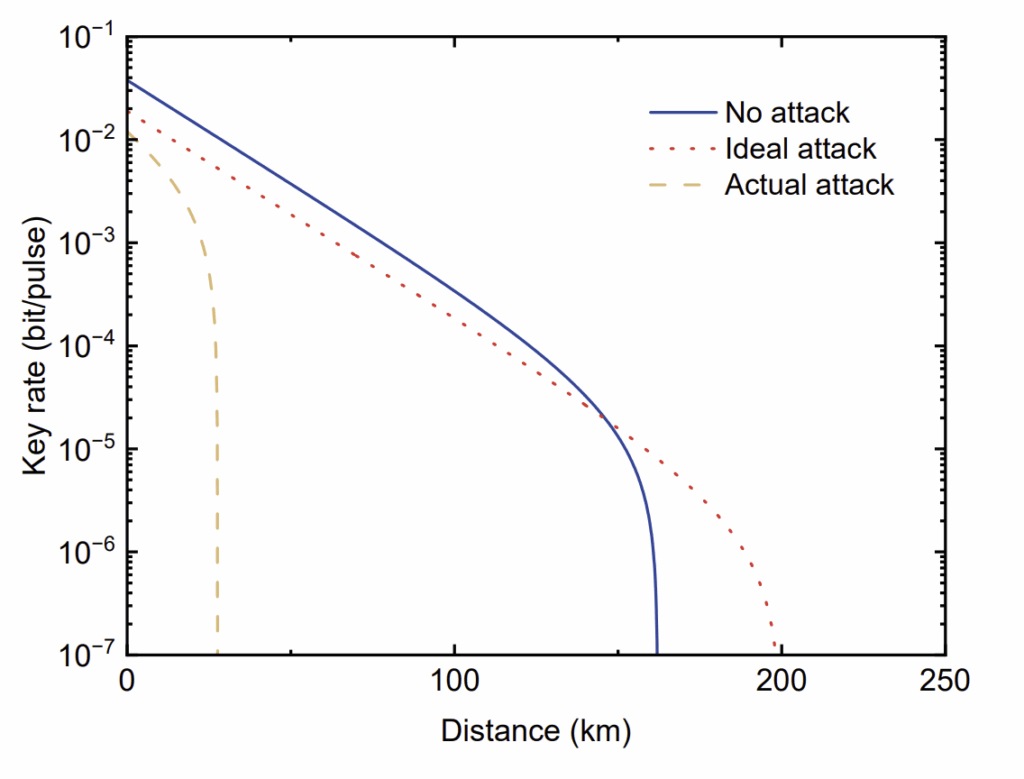

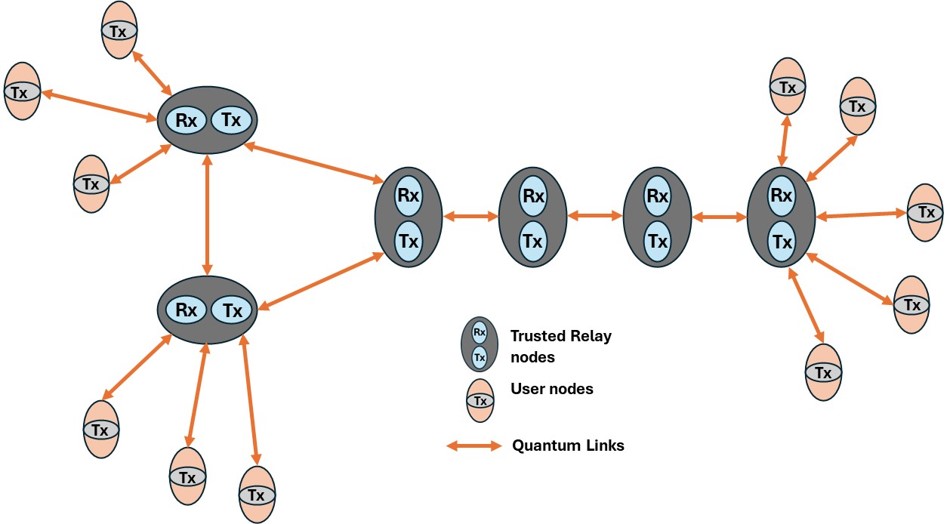

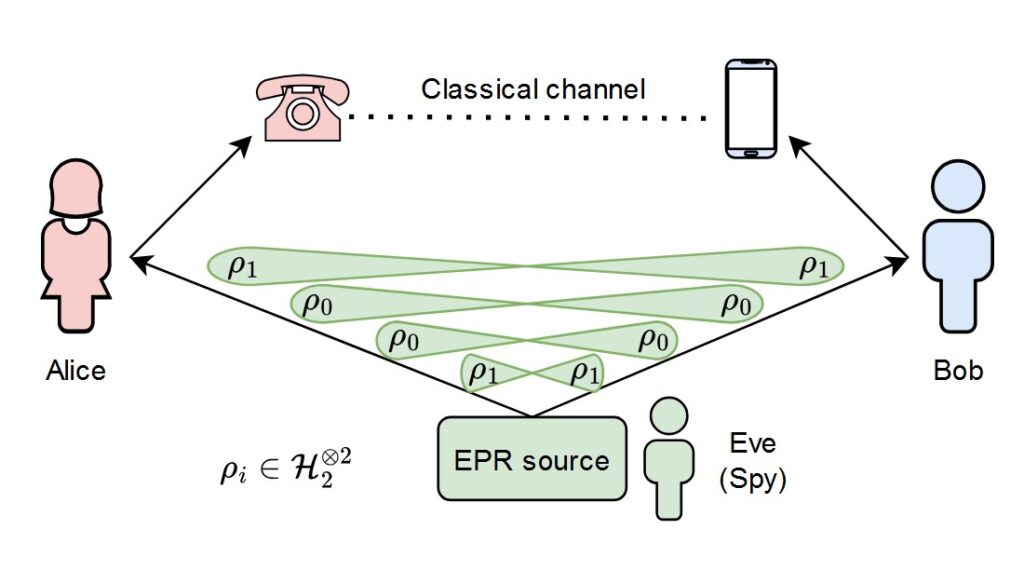

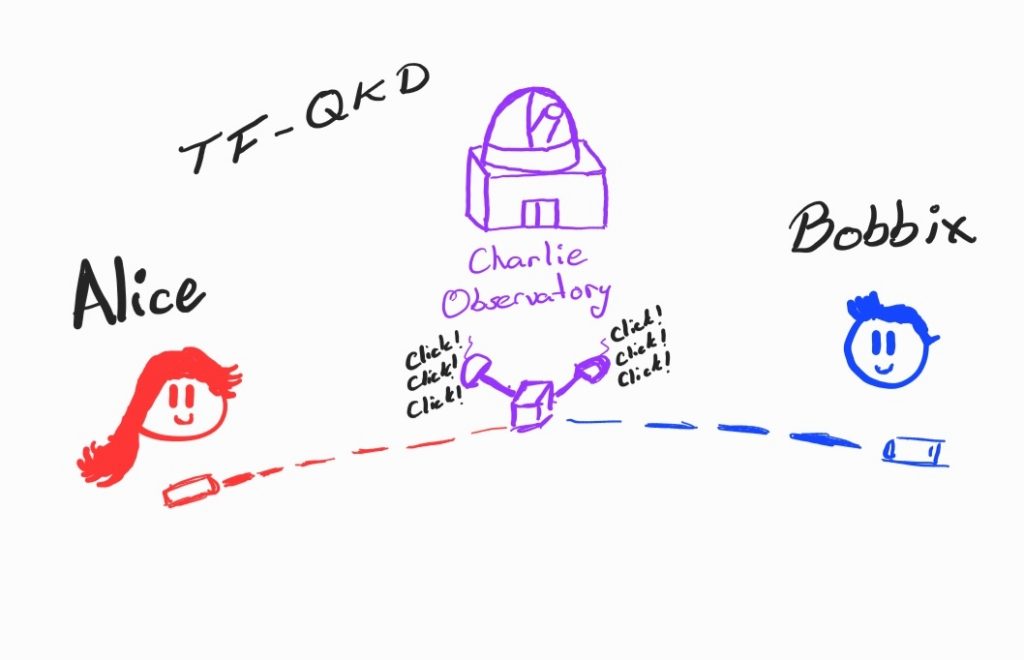

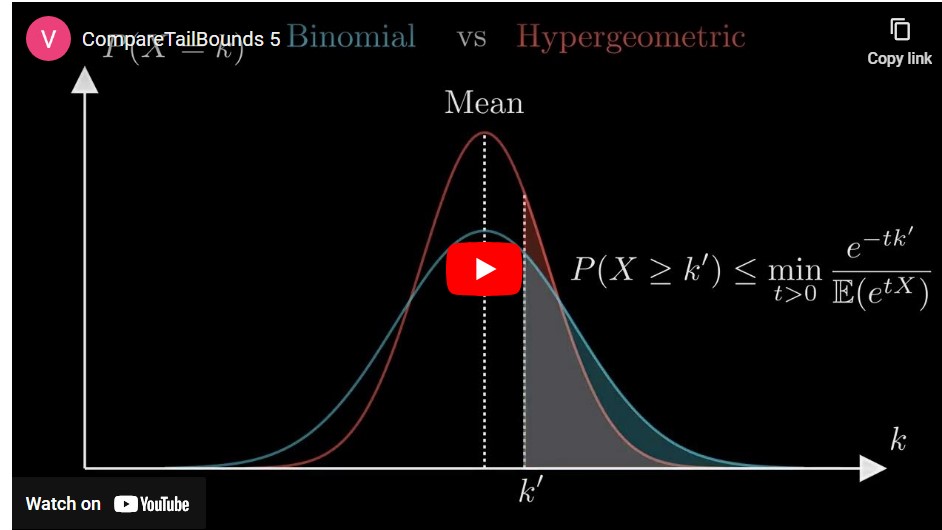

There are different ways of exploiting QEC for quantum communications. For instance, third generation quantum repeaters encode quantum state before transmitting them, and then perform error correction at every intermediate node.

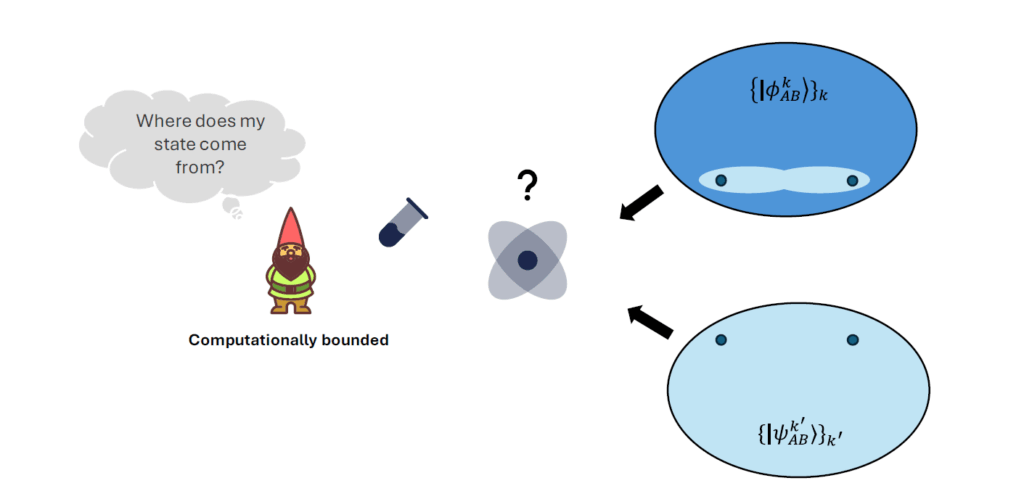

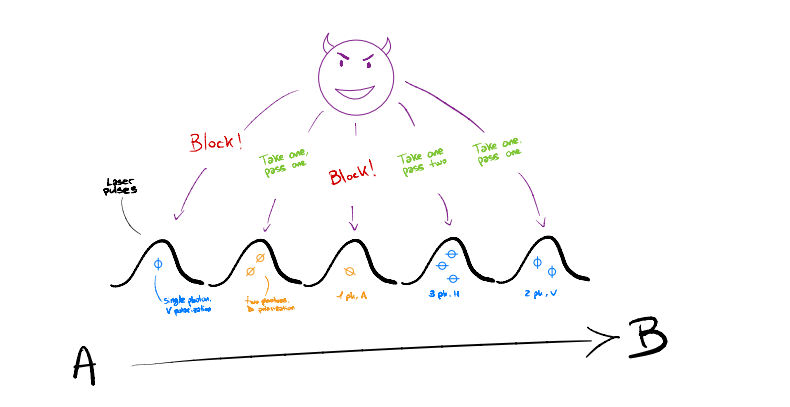

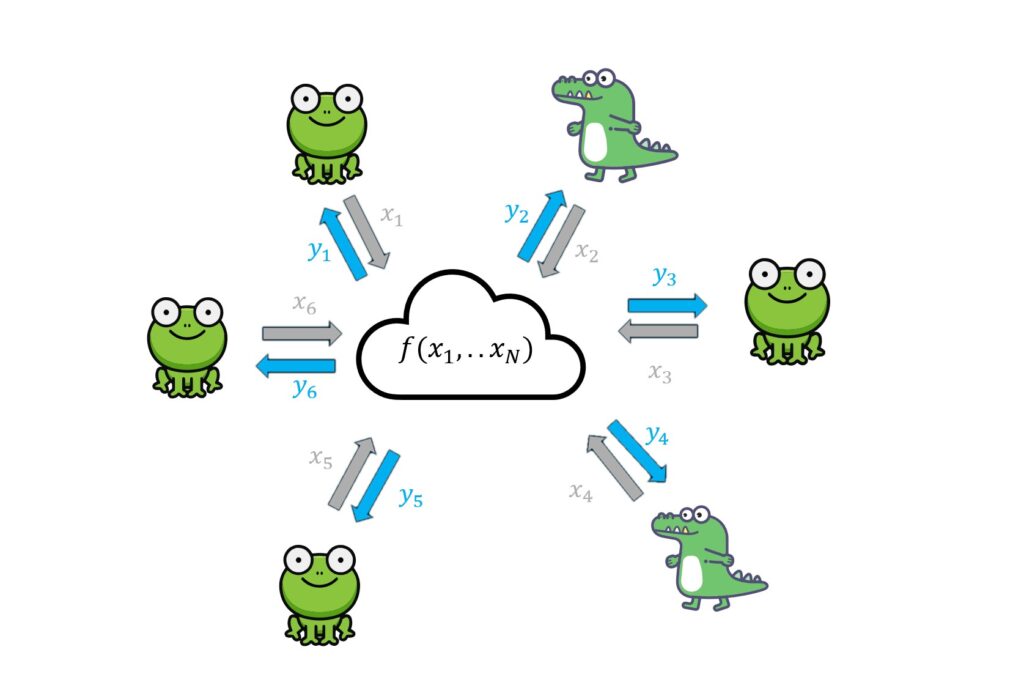

In my research, I focus on second generation repeater systems. In these, we start by generating entanglement using probabilistic methods, and then encode the entangled states into more robust, logical entanglement (the thick ropes in my 2025 story). From this, errors introduced during the swapping (i.e. connection) and storage of the entanglement may be identified and corrected.

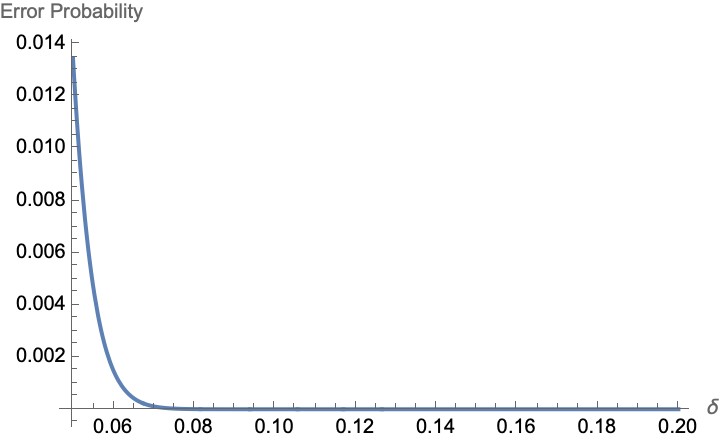

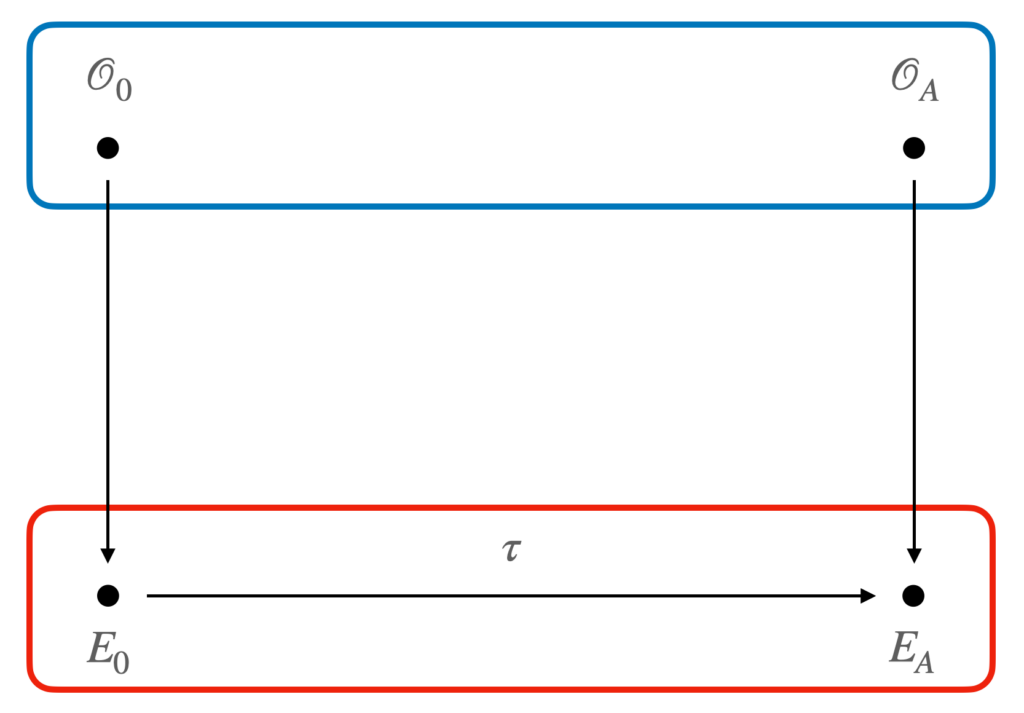

For my project, I look specifically at strategies using error detection. These strategies abstain from attempting to identify and correct errors and simply check whether any error has occurred. If we detect an error, we abort the entanglement distribution attempt and restart the process from scratch.

An advantage of the error-detection approach is that it requires less complex codes, possibly making it more appealing in the short term. Furthermore, it has been shown that, even after correction, distribution attempts where an error was detected remain prone to errors in some scenarios. Thus, our strategy can help focus network resources on attempts with a higher chance of success.

In the end, there is still much work to be done in the field of QEC, and in particular in how to exploit QEC to enable quantum communications. Nevertheless, this just makes it all the more exciting!

OTHER STORIES