STORY OF THE MONTH

About scalable entanglement distribution and ropes

Feb 2025

Feb 2025  Javier Rey Domínguez

Javier Rey Domínguez

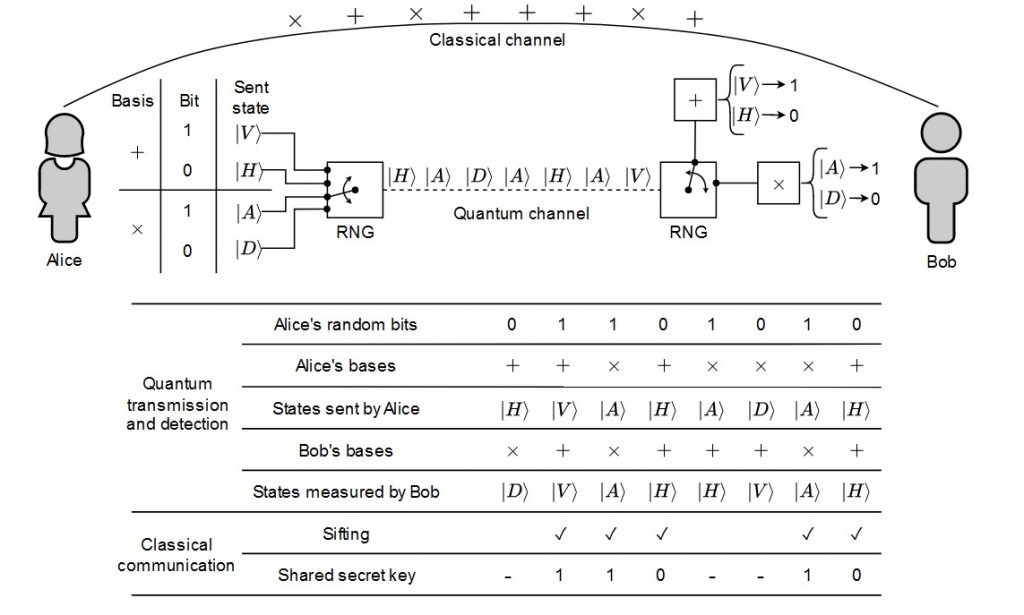

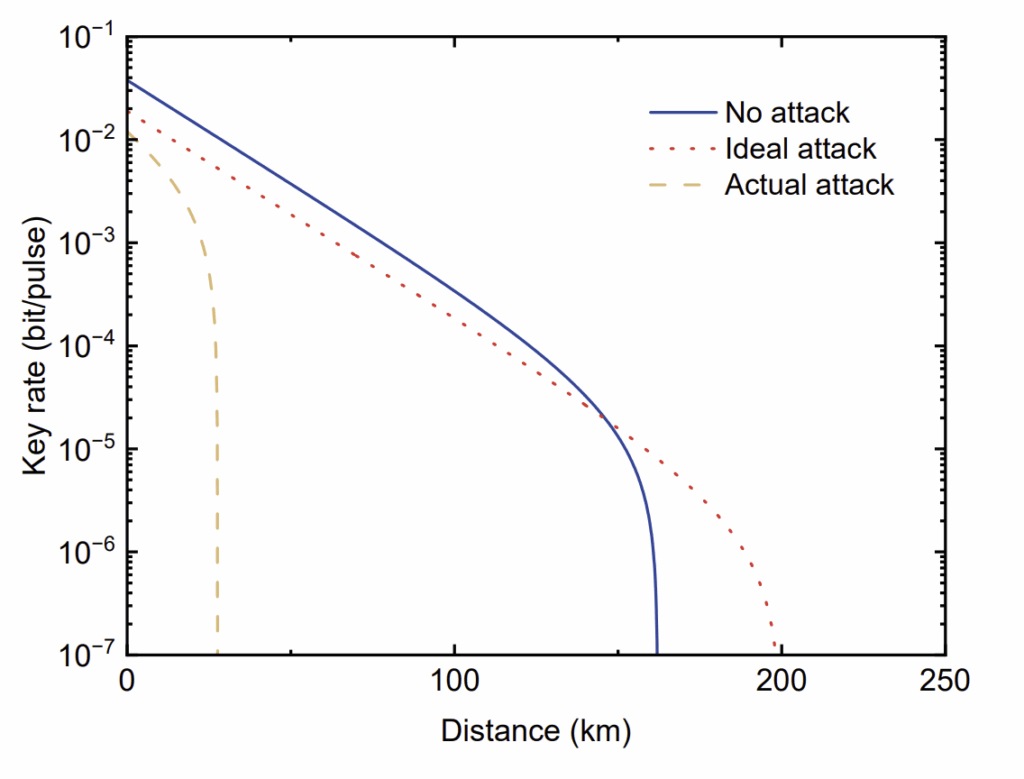

A few months ago, Matías taught us that we can exploit quantum entanglement to distribute secret keys in a secure way. Indeed, entanglement distribution is one of the key primitives of quantum communications networks. In this month’s story, we will cover the basic building blocks that can be used to enable this task at arbitrarily long distances.

The nature of entanglement

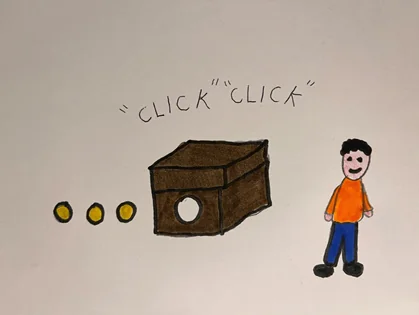

Entanglement is nothing more than a type of correlation which is stronger than what can be achieved classically. We can think about it like an imaginary rope tying two coins together. Once we flip these coins, it does not matter what the specific results are, but we know that they will both be correlated. In this case, they can be directly correlated (they are both heads or both tails) or anticorrelated (one head and one tail).

Clearly, any adversary that can only see the rope has no information about the actual results of the coin flips. Moreover, two users (say, Alice and Bob) can read some coin flips and, exploiting the knowledge about the correlation between the coins, agree on a secret key without revealing anything else.

Generating entanglement between two connected nodes

But how do we prepare this correlation? In practice, there are several ways in which this can be done in a lab, but how do we go from this to the useful entanglement of distant parties? We discuss now a way to do this.

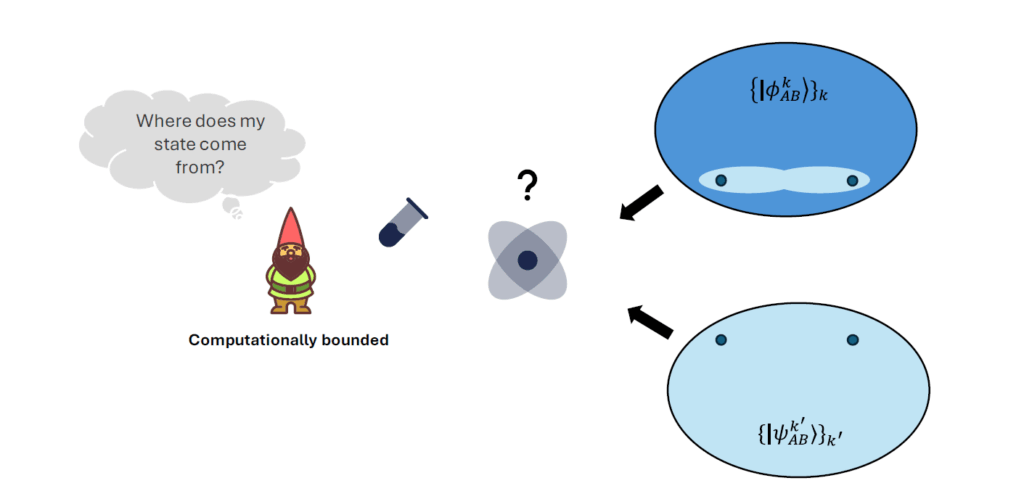

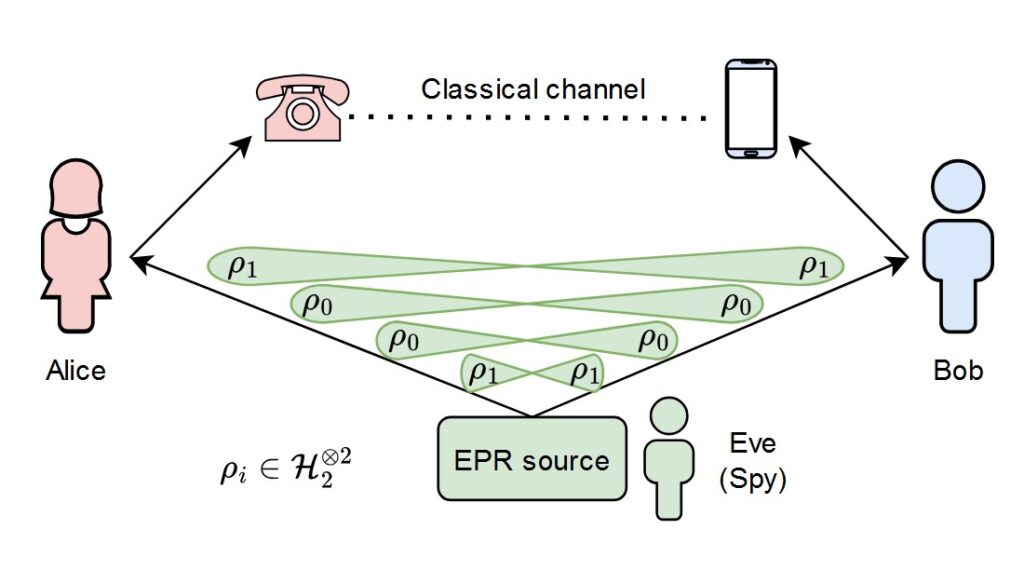

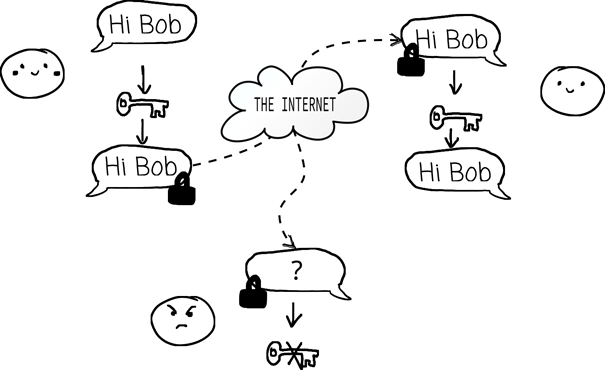

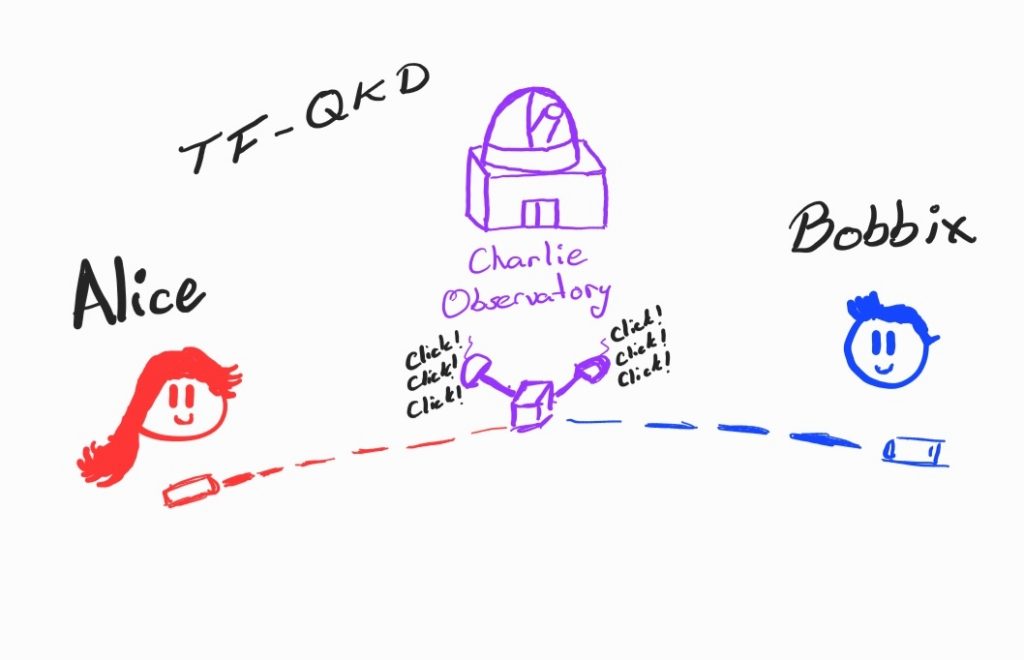

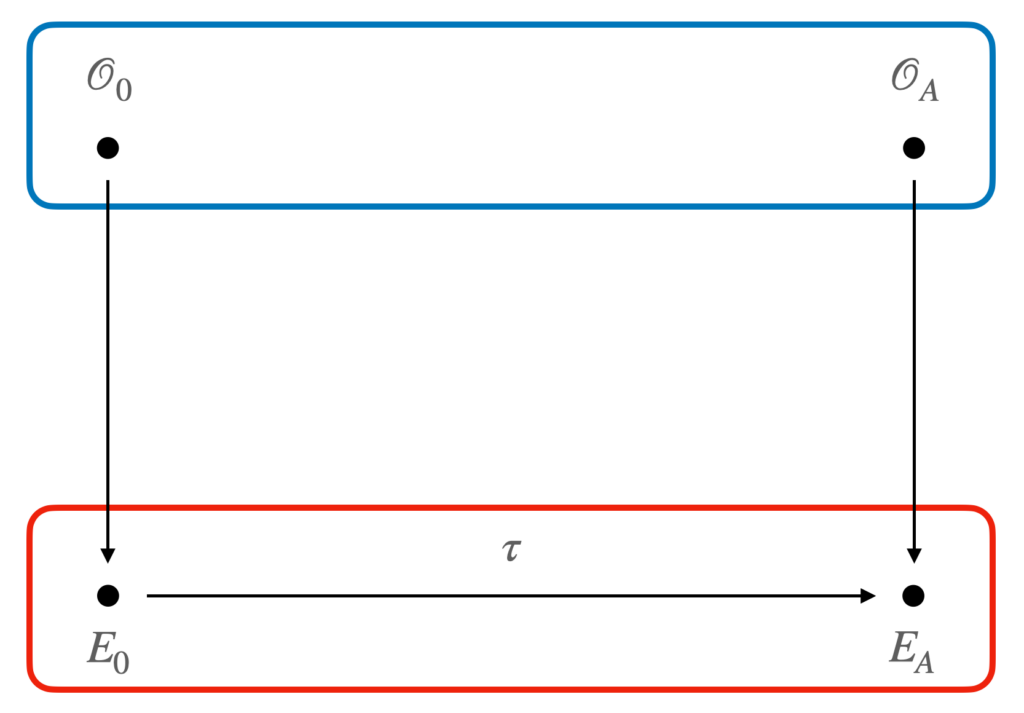

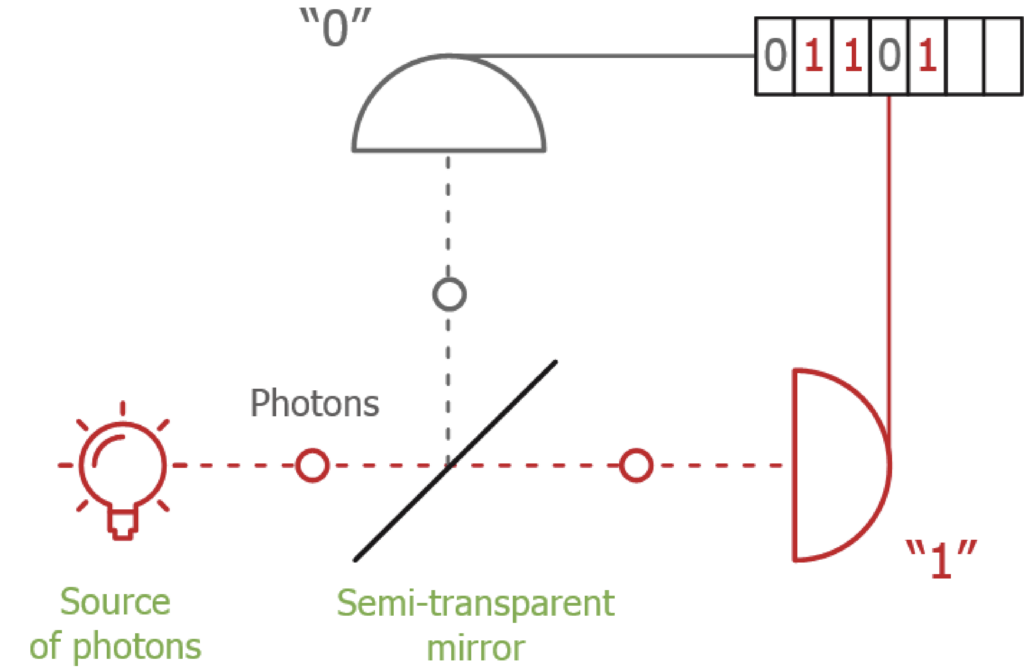

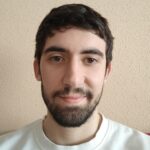

First, Alice and Bob each prepare entanglement between a quantum memory (that is, particles which can hold a quantum state for a long time) and a photon, and they transmit the photons towards each other through a quantum channel (for instance, this could be an optical fibre). Think of this step as attaching a rope between each coin and a rock, and then throwing the rocks towards each other.

At some point in the middle (this can even be in one of the labs, in the most asymmetric case), a type of measurement called Bell state measurement (BSM) observes the interference between the photons. If the photons are correctly observed, the coins are projected into an entangled state. In a way, somehow, we have received the rocks with both ropes and tied them with a knot. What’s more, the BSM tells us the type of correlation that we are dealing with, and so that information can be relayed to the users though classical channels.

Figure 1: A meet-in-the-middle setup for entanglement generation. Above, the entanglement is generated between the memories and the photons, and the latter are sent through the quantum channel (solid lines with a loop). Then, they interfere at the midpoint and a BSM is performed. The results are transmitted to the nodes through classical channels (double lines).

Notably, this operation can fail. Firstly, the probability of receiving a photon at the end of a physical channel decreases rapidly with its length, so it might be that one of the rocks (photons) that we threw (sent) just did not make it. Secondly, the BSM itself can fail, for instance if the photonic detectors do not click despite receiving the photons. A way to solve this issue is to use the oldest trick in the book: just try again (or as we call it, repeat until success).

Extending entanglement

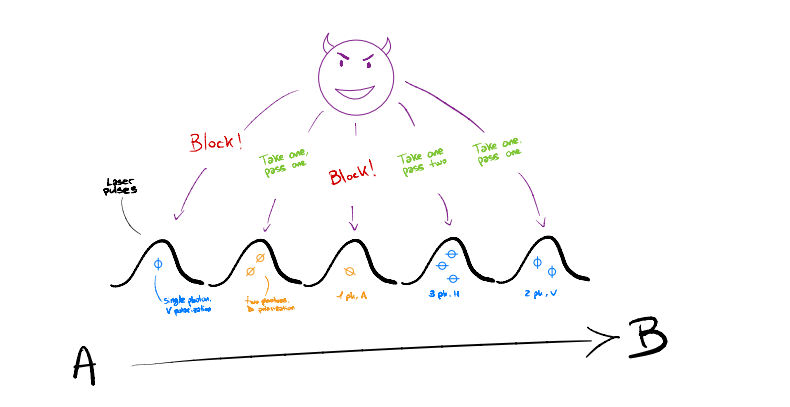

That is all fine and dandy, but we just said that the probability of receiving photons decreases very quickly with the length of the channel. What if Alice is in London and Bob in Hong Kong? Is this method still enough? Are Alice and Bob Dragon Ball characters, capable of throwing rocks all around the globe? Clearly, we need to think of something smarter.

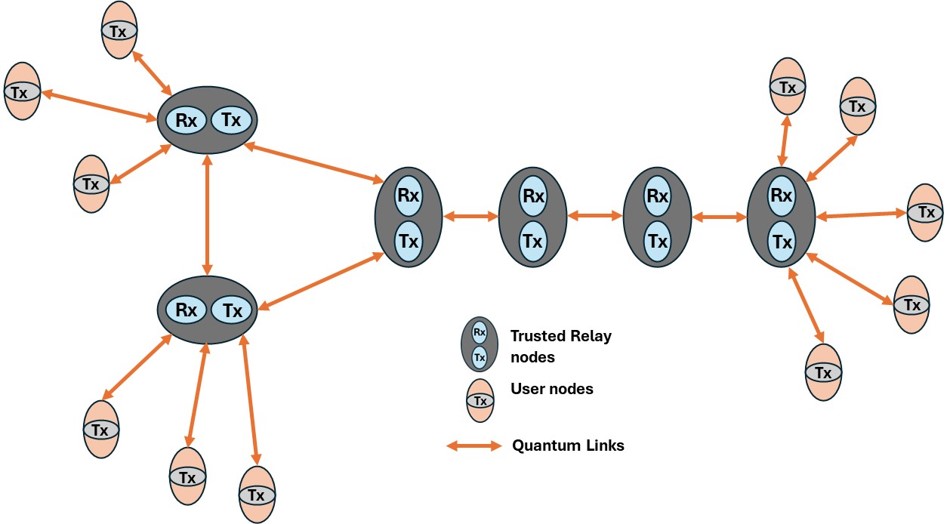

What we do here is to call our old friends, the quantum repeater nodes [1]. Essentially, if we have a path of nodes from one user to the other, we can simply generate short segments of rope (entanglement) between each subsequent pair of nodes (including the users at the tips of the chain). Then, each repeater node performs a BSM and announces its result. You can think about this like each of these friends tying a knot in two ropes and deducing, from their type of correlations, how the coins at the other tips of the rope are correlated. After some classical signalling, we have an end-to-end rope and we know which type of correlation it represents.

Noise

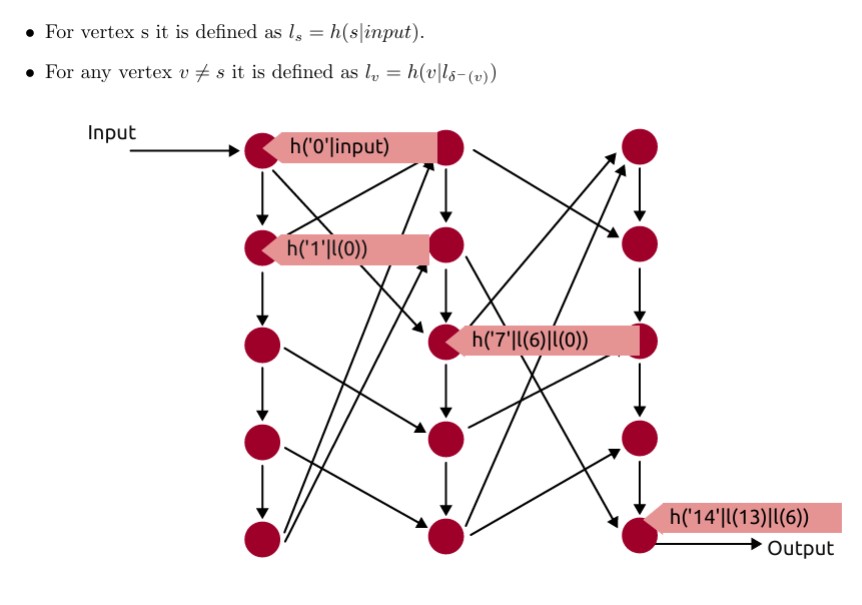

A big assumption that we are making here is that we always know exactly the type of correlation that we have. However, this may not be the case. For instance, we might not be very confident in the results from the BSMs. What is more, the quantum properties of particles suffer from decoherence over time, which can also degrade our confidence in the correlation. There are several methods to deal with this noise, and they largely determine the type of repeater that we are dealing with.

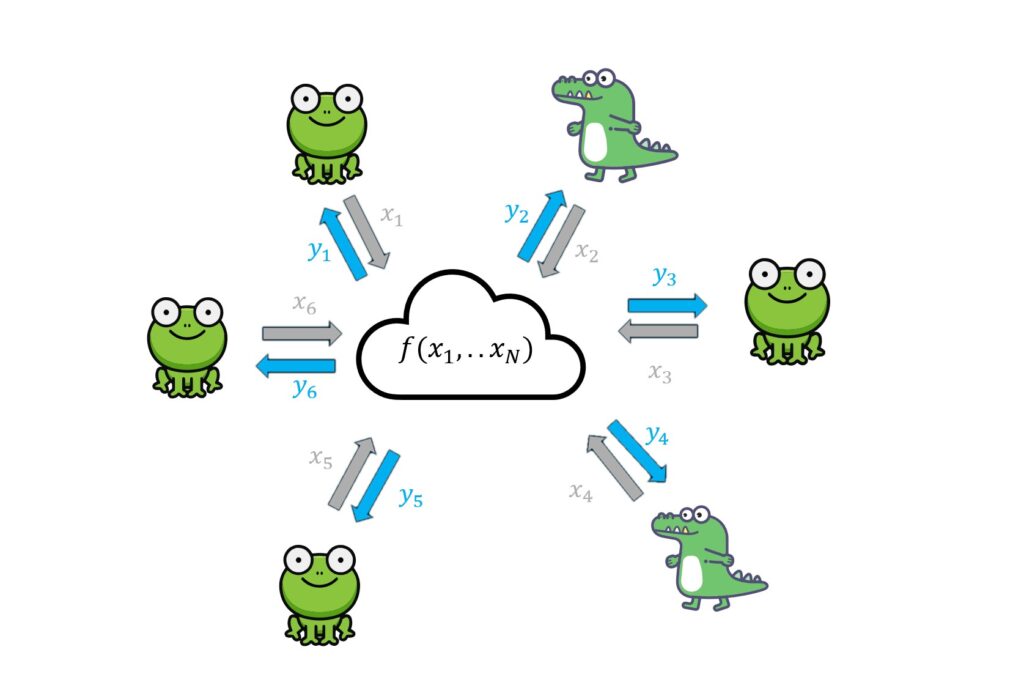

On one hand, entanglement distillation [2] can be seen as distributing several ropes, somehow comparing their correlations and then measuring the coin flips of all but one rope. If the measurements make sense, then you are more confident in the remaining rope’s entanglement. If they do not, you simply discard your rope and start again. Distillation is a simple technique that may be available to use in the first quantum repeaters, but its probabilistic nature can limit its maximum performance.

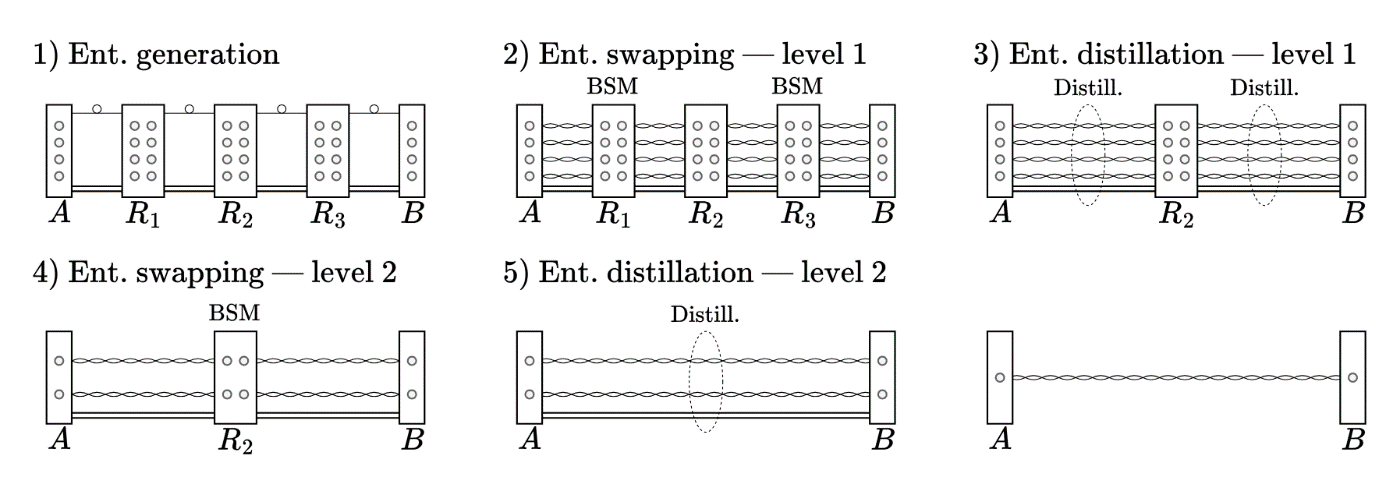

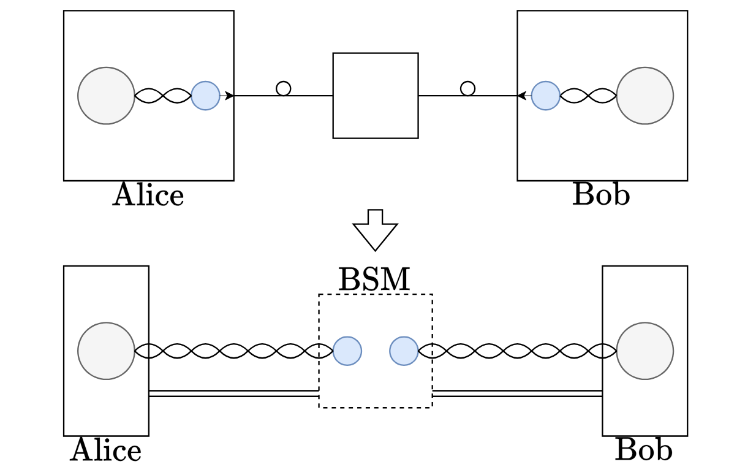

Figure 2: the original proposal for a quantum repeater protocol [1]. Several rounds of distillation and swapping (tying the knots) are iteratively performed, and finally a single high-quality link is obtained.

A different method, typical of second-generation repeaters [3], is using encoded entanglement. Essentially, you prepare a bunch of ropes at each segment of the path, and then intertwine them together to construct a single, more robust rope. Then, you simply keep extending the rope by tying somewhat complex nodes. Eventually, Alice and Bob need decode the end-to-end rope to obtain a single entangled link with high confidence. This method requires more specialized equipment but may offer better results in some scenarios.

A third, more complex method is to use quantum error correction for the entanglement generation in the first place. That is, rather than transmitting two entangled photons and measuring their interference, Alice (for instance) simply ties a rope from her coin to a drone and sends the drone forward. Unfortunately, quantum error correction is much more limited than its classical counterpart in the amount of losses that it can sustain, so our drone is equipped with a very small fuel deposit and we need repeaters anyways. In fact, these repeaters [4], which act as refuelling stations for the drones, need to be at even shorter distances than the repeater nodes based on the other strategies, which may drive up the cost, not to mention the high technological complexity. Nonetheless, one-way repeaters based on error correction might one day offer the highest performance, thanks mainly to the fact that they do not rely on repeat-until-success strategies.

Conclusion

Now, this is just a simplified view of how quantum repeater-powered entanglement distribution might work. However, we have glossed over some important topics, like order of operations and multi-user networks, that we may leave for another month.

[1] H. J. Briegel et al. “Quantum repeaters: The role of imperfect local operations in quantum communication”. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81.5932 (1998).

[2] C. H. Bennett et al., “Purification of noisy entanglement and faithful teleportation via noisy channels,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 76.722 (1996).

[3] L. Jiang et al., “Quantum repeater with encoding”, Phys. Rev. A 79.032325 (2009).

[4] W. Munro et al., “Quantum communication without the necessity of quantum memories”, Nature Photon 6, 777–781 (2012).

OTHER STORIES